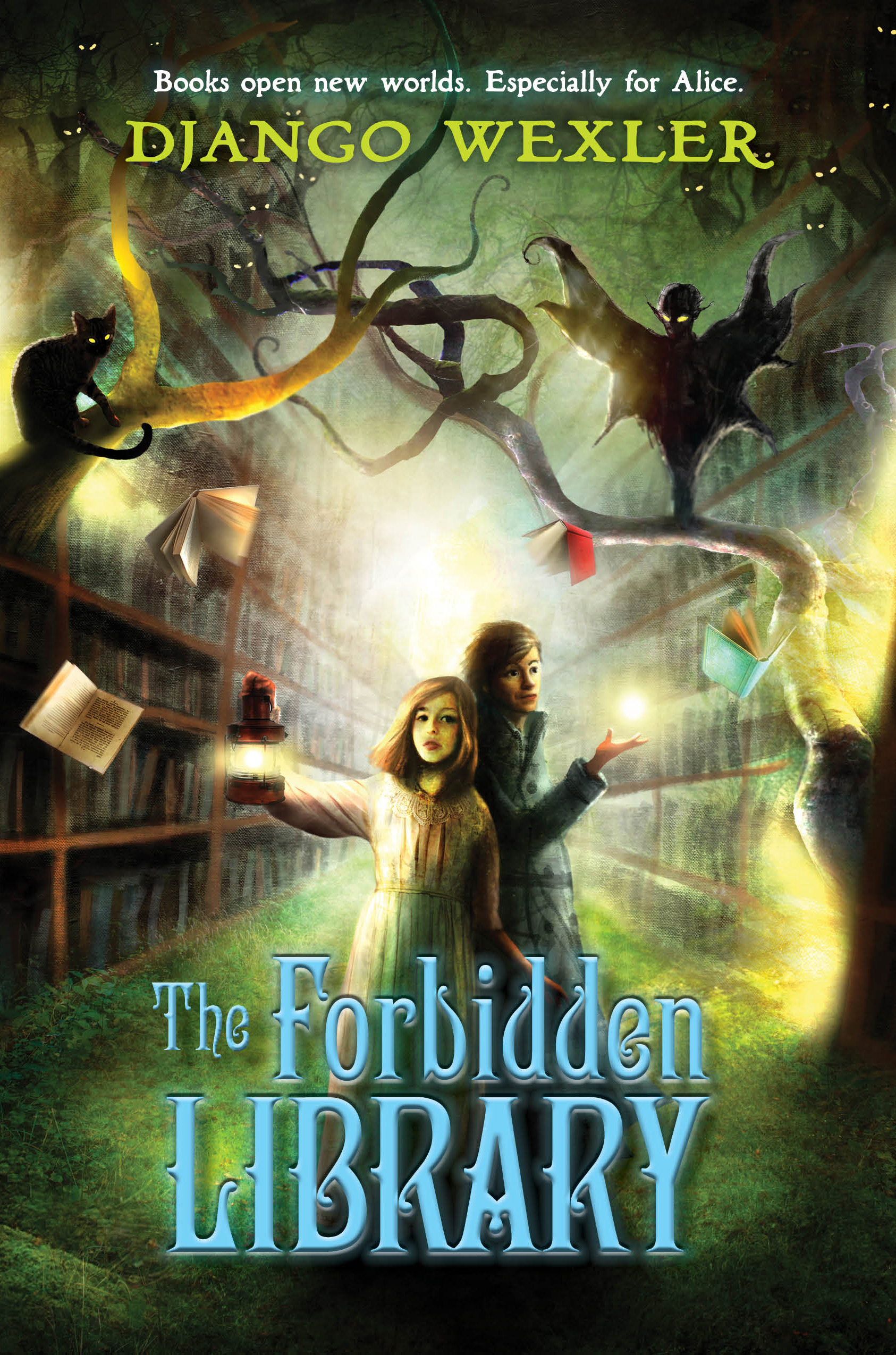

The Forbidden Library – Excerpt

PDF Version

You can read Chapter One as a PDF, with all its lovely formatting and images. For those who prefer the web, I’ve copied the text here, but be sure to check out the book to see what you’re missing!

The Forbidden Library

Chapter One

The Fairy

Much later, Alice would wonder what might have happened if she’d gone to bed when she was supposed to.

It was a fluke, really, because she was the sort of girl who almost always followed the rules. But she’d been doing schoolwork and she’d lost track of time.

It was a Saturday night, and her tutor, Miss Juniper, had assigned her another chunk of algebra for Monday morning. Alice excelled in all her subjects — she never would have allowed it to be otherwise — but in algebra her excellence was born of hard work and long hours rather than natural talent, so she’d determined to make an early start. She wouldn’t be bothering anyone, either. Her room had its own little writing desk and even its own electric lamp, which her father had had installed three years before with the boast that no daughter of his was going to ruin her eyes scribbling by gas-light.

Her father had been working late again. When Alice heard the tell-tale creak of the front door, she weighed the odds and decided he’d probably be happier to see her than he was angry that she was still up. She shrugged into her robe and padded into the hall and down the stairs.

The late-night silence was a little unnerving. Alice had grown up in a house that had practically bustled with servants and guests, even in the middle of the night, and she was used to seeing strangers about. But the servants had departed one by one as times had grown mean, until only Cook, Miss Juniper, and her father’s man were left, and the visitors were less common than they used to be. The guest rooms that lined the hallway were all shut up now, with sheets draped over the furniture.

She passed the doors quickly, tugging her robe a little tighter, and ducked into the servants’ stair that led to the kitchen. Her father would probably be there, fixing himself something hot to drink.

Sure enough, the swinging door at the bottom of the steps was outlined in yellow light. Alice put her hand out to push it open, but as her fingers brushed the wood she heard the voices, and realized her father wasn’t alone.

“…you have to know what we can do for you, Mr. Creighton,” said someone who wasn’t her father. “Someone is going to take advantage of it sooner or later.”

Alice turned away at once. Being up late was one thing, but eavesdropping on her father’s business conversations was quite another. She’d put her foot on the first step when the sound of her father’s voice brought her up short.

“Don’t you dare!” he shouted. “Don’t you dare threaten my family.”

The words hung in the air for long seconds, like a fading firework.

Her father never shouted, at least not in her hearing. He was a quiet, honest man who dealt fairly with everyone, put flowers on her mother’s grave once a month, and went to church every Sunday. Hearing him talk like that was like watching a teddy bear yawn and reveal a mouth full of fangs. Alice stood perfectly still, not daring to move even her eyes. She wanted to run, knew she ought to—whatever was being said was obviously not for her ears—but her feet felt like lead weights.

“Mr. Creighton,” said the other man. “Nobody’s threatening. I’m just stating a fact. Nothing wrong with stating a fact, is there? No law against it.”

His voice was odd, high and nasal. Alice could hear a strange sound as well, a kind of urgent thrum-thrum-thrum.

“Don’t mess me around,” her father said, not shouting now but still angrier then she’d ever heard him. “We both know what you’re here to say, and I’m sure you know what my answer’s going to be.”

“I strongly recommend you reconsider your position, Mr. Creighton.” The thrumming grew louder. “For the sake of everyone involved.”

“By God,” Alice’s father said. “So help me, I ought to break your ugly head against the wall.”

“You could do that,” the other man said. “You could do that, Mr. Creighton. But you won’t. You know it would be unwise.” His voice dropped a fraction. “For the girl, most of all.”

Slowly, ever so slowly, Alice turned around. Her heart was still beating so hard it seemed a wonder that her father couldn’t hear it. She stepped back down to the door, carefully avoiding the creaky step, and pressed her fingers into the crack of light. It was wrong, possibly the most wrong thing she had ever done in her entire life, but she had to see. She gave the swinging door the lightest touch, and the crack widened into a gap big enough for a garter-snake, to which she applied her eye.

The light made her squint. On one side of the room was her father, still in his suit, looking rumpled. His hair was damp with sweat. One of his hands was curled around the handle of a cast-iron frying pan sitting on the range, as though he meant to swing it and make good on his threat.

Across from him, hanging in the air, was a fairy.

When Alice had been a little girl, her father had given her a book called The Enchanted Forest. It was a big book made with thick paper, and had large type with pen and ink illustrations on each facing page. She’d probably been a bit too old for it, truth be told, but she’d read it anyway, as she read every piece of printed material that fell within her reach. It was the story of a rather stupid little girl who wandered into an enchanted forest, and caused a good deal of havoc among the creatures who lived there.

One of those creatures had been a fairy. It was a slim, child-like figure with wide eyes and a button nose wearing flowing clothes, held aloft by gauzy insect wings — Alice had always imagined the wings in translucent greens and blues, like a butterfly’s — and it had looked down at the little girl with an air of amused benevolence while it stood daintily in her raised palm.

At that age, Alice had grasped the idea that some things in books were real, and others were not. Questioning her father had revealed that there were such things as lions, tigers, and elephants (he’d promised a visit to the zoo, which had yet to happen) while trolls, centaurs, and dragons were the figments of writers’ overactive imaginations. Alice remembered feeling vaguely annoyed at the author of The Enchanted Forest, who had clearly intended to deceive little girls possessing less penetrating intellects than her own.

There was, her father had told her, no such thing as fairies, either.

The thing hovering in the air in Alice’s kitchen was similar enough to the picture in the book to be instantly recognizable, but it was larger, for one thing. The creature in the book had been insectile, six inches high at most, while this creature was a good two feet from head to heel. Its wings were enormous, considerably bigger than its slender body, and beat the air so fast they were a blur, like a hummingbird’s. They were colored, not in greens and blues, but yellow, red, and black, which put Alice in mind of something nasty and poisonous.

The fairy’s skin was off-white and gnarled with warty growths sprouting clusters of thick, black hair. Its scalp was bare and bald as an egg, gleaming wetly in the electric light. It had no nose at all, and its eyes were wide but black from edge to edge. When it spoke, she could see a mouth full of needle-like teeth, and a long red tongue like a snake’s.

Alice closed her eyes. This, she thought, is ridiculous. There are no such things as fairies. She gave herself a pinch on the arm, which hurt, and counted slowly to ten.

When I open my eyes, she thought, it will be gone.

“I really wish you’d at least hear my offer,” said the nasal voice.

Alice opened her eyes. The fairy was still there. It had hovered closer to her father, its wings thrum-thrumming, one tiny finger wagging in under his nose.

“I will not,” Alice’s father said. “I will not entertain any sort of offer. Go back and tell your master that. And tell him, if he troubles me again, I’ll …”

The fairy waited, lip curled in a cocky grin that showed its teeth. “You’ll what, Mr. Creighton?”

“Get out!” he shouted. “Get out of my house!”

There was a long moment of silence. The fairy hovered, impudently, as if to demonstrate that it didn’t have to go just because her father had said so. Then, with an affected sigh, it spun in the air and zipped out the open doorway on the other side of the room. Alice heard one of the front windows rattle open.

Her father sagged, like a heavy weight had been fastened around his shoulders. He let go of the frying pan and leaned on the range for support. Alice wanted to run to him, but she didn’t dare. Whatever she had just seen — and she was still not certain what she had just seen — it was something she had not been supposed to witness.

Alice’s father took a long breath, closed his eyes, and blew it out slowly, tickling the edges of his mustache. Then his eyes snapped open, full of panic.

“Alice,” he said, under his breath. “Oh God.”

All of a sudden he was running, struggling to get his feet under him, caroming off the kitchen doorway and out toward the main stairs. Alice was caught for a moment in stunned surprise, then started running herself, back up the servants’ stairs, heedless of the creaking. He made it to her door only a few seconds before she arrived.

Finding the door slightly open, he flung it ajar, and stared wide-eyed at the empty room. His expression, bathed in the glow of her electric desk-lamp, was the most terrifying thing Alice had ever seen.

She hurried to his side and grabbed his arm. “Father! Is something wrong?”

“You –” He gestured weakly at her empty room, then down at her. “I thought –”

“I was studying,” Alice said, “and I got up for a moment. I’m sorry if I startled you.”

All at once his fierceness melted, and he wrapped his arms around her in a hug so tight he lifted her off the ground.

“Alice,” he said, his scratchy cheek pressed against her forehead. “Alice.”

“I’m here, Father.” She squirmed until she worked her own arms free, then put them around him as far as they would go.

“It’ll be all right,” he said. She wasn’t sure if he was talking to himself or not. “Everything is going to be all right.”

“Of course it is,” she said.

When he let go, there was something new in his face, a fierce, wild determination so far out of the ordinary that it made Alice feel scared and proud of him, both at once. Her set her down gently, put his hands on her shoulders, and looked her in the eye.

“I love you,” he said. “You know that, don’t you?”

Alice felt herself blushing. “Of course.”

His eyes were already miles away. He patted her shoulder, absently, and then got up and hurried toward his study. Alice looked after him, wondering about the decision she’d seen in his eyes.

Then, because she was a girl who followed the rules, she went back into her room and went to bed.

The next morning, everything seemed so normal that Alice almost thought she’d dreamed the whole thing. Almost, but not quite.

She woke up in her familiar bed, under her warm, familiar quilt with its frayed edge. Her room was just her familiar room, with the heavy oak wardrobe in one corner and the framed picture of her grandmother looking down benevolently.

There was no elf sitting on her desk, and her books were just where she’d left them the night before. No troll in the heavy wooden chest at the foot of the bed, only the winter comforters and an ancient pair of stuffed rabbits she couldn’t quite bear to throw away. She even, feeling intensely self-conscious, lifted the bedskirts and looked underneath, but there was no dragon there, only a thick layer of dust.

Nevertheless, she was certain what she’d seen had been real. The memory was bright and clear, not fuzzy and fading the way dreams were. When she sat down for breakfast with her father, she became doubly sure. He was acting normal, but it was an act, a little too sincere to believe.

“Earthquakes again,” he said, paging through the Times. “First New Zealand, now Managua. Thousands dead, it says.”

“That’s terrible,” Alice said, because she knew it was expected of her. She was trying to keep from staring at her father’s face. He’d washed and shaved since last night, of course, but there were still something tight around his eyes. It wasn’t a dream, she thought. I’m sure of it.

“Something ought to be done about it,” he said, turning the page. “And still fighting in Spain. Seems like the whole world’s coming to pieces.”

“You always say they only print the bad news,” Alice said.

Her father looked up and smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes.

Cooper, her father’s man, appeared with a plate of toast and jam. Properly speaking, it wasn’t his job to serve at table, but Alice’s father had been forced to give the last of the footmen the sack when they’d caught him stealing from the pantry. Cooper insisted he didn’t mind. In this day and age, he said, a man ought to be grateful to have work at all.

Her father put the paper aside and went to work on the toast, all in silence. Alice took a slice herself and carefully covered it with jam, right to the edges, working carefully with the butter knife to spread it evenly. The longer neither of them spoke, the more the silence grew and grew, like some monstrous thing squatting on the table between them. When her father finally cleared his throat Alice gave a little start.

“Alice.”

“Yes, Father?”

“I’m going on a trip.” He paused, and took a deep breath. “Something’s come up. It’s important, I’m afraid.”

“When?” Alice said. “And how long will you be gone?”

“I’m catching a steamer tonight.”

A ship? Her father’s business took him all over New England, and occasionally as far as Chicago or Washington, D.C., but he’d never been gone for more than a week, and never on a steamer. “And where –”

“Here.” He folded the paper and pushed it over to her. “It’s the Gideon, bound for Buenos Aires.” The schedule, a set of stops all down through the Caribbean and South America, was printed in a neat box beside the ticket prices and number for inquiries. “This way you’ll be able to keep track of me.”

Alice put one hand on the paper and swallowed hard, trying to sound as normal as she could. “When should I expect you back?”

His expression cracked. Just for a moment, but Alice was watching him closely, and she knew him better than anyone. His mouth turned down, pulling at his mustache, and his eyes glittered with tears.

“It’ll be some time,” he said. “I’m sorry, Alice. I wish there was another way.”

Something was wrong, very wrong. Alice fought a growing thickness in her throat.

“Perhaps I should come with you,” she said. Ordinarily she wouldn’t have dreamed of offering such a suggestion unbidden, but desperate times called for desperate measures. “You’ve always said I need more experience in the practical side of business –”

“No,” he said, a little too quickly. “Not this time. When I get back …” He forced a smile. “Maybe then it’ll be time for you to start making the rounds with me. In the meantime, I’ll make sure to send you a postcard from every stop.”

The following day, Miss Juniper moved into one of the guest-rooms and added looking after Alice to her tutoring duties, although in truth Alice didn’t take much looking after. She worked on her French, and her algebra, and completed everything she was assigned on time. When Miss Juniper asked her what she wanted to do for her day off, Alice told her that she wanted to go to the Carnegie Library. She spent eight solid hours there, a solemn girl alone at one of the great wooden reading-desks, working her way through a stack of books that represented everything the library had on the subject of fairies.

Her father needed her help, she was certain of it. She wasn’t sure why, or how, but the brief glimpse of the fairy in the kitchen was all she had to go on. She took home a notebook full of references and scribbles, and as many books as the librarian would let her have. She stayed up late reading that night, and the night afterward as well. Alice was not a girl who believed in half measures.

Two days later, Cooper brought her the Times with breakfast. The front page told her that President Hoover had given another speech promising that the worst was over, that the stock market had taken another tumble, and, below the fold, that the steamer Gideon had gone down in a freak storm off Hatteras, with all hands.